The Ground Still Glows: The Scary Reality of Nevada’s Nuclear Test Sites

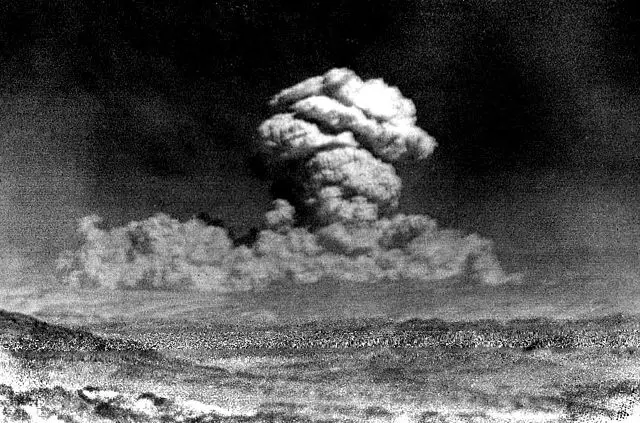

Picture this: a desert sunrise over Nevada in the 1950s, but instead of peaceful stillness, there’s a blinding flash. A mushroom cloud rises like an apocalyptic flower, and somewhere nearby, soldiers are crouching in trenches, watching the sky boil.

That was real. It happened dozens of times. And the ground still remembers.

Welcome to the Atomic Playground

Between 1951 and 1992, the Nevada Test Site (now the Nevada National Security Site) became America’s nuclear sandbox. Over 900 nuclear tests were conducted there. Above ground. Below ground. In towers, in tunnels, in the open desert.

The U.S. was in a race. With the Soviets. With fear. With itself. And the Nevada desert was the perfect “remote” place to flex nuclear muscle without international consequences.

Except there were consequences. They just landed on American soil.

The Town That Watched the Bomb

Las Vegas was only about 65 miles away. And for a while, they leaned into it. Tourists came to watch the explosions. Hotels advertised blast-viewing breakfasts. Souvenir shops sold mushroom cloud merch. People would drive into the desert, set up picnic blankets, and stare straight into nuclear detonations like they were fireworks.

It’s surreal to think about now. But back then, it felt like progress. Like power. Like America winning.

Fallout and Denial

The problem? Radiation doesn’t care about borders, or optimism, or televised countdowns. Winds carried radioactive fallout into Utah, Arizona, and even parts of the Midwest. Sheep died. Cancer rates spiked. And for years, the government insisted everything was fine.

Documents later revealed that officials knew more than they admitted. Tests had shown the danger. But secrecy won out.

They called it “downwind syndrome.” Thousands of civilians exposed without warning or consent. Soldiers too. Many of them were stationed near test sites to study the effects of atomic blasts on the human body.

Survivors Speak Up

Some of those soldiers lived to tell their stories. Others didn’t.

Veterans and civilians began organizing in the 1970s and 80s. Their message was simple: we were used. We were lied to. We deserve justice.

In 1990, the U.S. government passed the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), offering some financial restitution to victims. It helped. A little. But for many, it came too late.

The Craters Remain

If you visit the Nevada National Security Site today, you can still see the scars. Craters. Fenced-off zones. Radiation warning signs. A haunting monument to an era when glowing sand and shattered earth meant national pride.

There’s even a massive hole called Sedan Crater, created by a test meant to explore whether nuclear bombs could be used for mining. Spoiler: they made a giant pit and a radioactive mess.

What We Choose to Forget

We like to think of nuclear disasters as something that happened “over there.” Chernobyl. Fukushima. But the Nevada desert holds a quieter, more deliberate legacy. One made in labs, authorized by presidents, cheered by crowds, and paid for in silence.

And that silence lingers. Many younger Americans don’t know we tested hundreds of nukes on our own soil. Or that families in downwind areas are still dealing with strange cancers, still wondering if that dust in the wind ever really settled.

There’s even a massive hole called Sedan Crater, created by a test meant to explore whether nuclear bombs could be used for mining. Spoiler: they made a giant pit and a radioactive mess.

So, Why Talk About It Now?

Because we forget too easily. Because the next time nuclear weapons are mentioned, it shouldn’t just be about strategy or deterrence. It should also be about consequence. About people. About land that still glows.

Not metaphorically. Literally.

Sources:

1. U.S. Department of Energy: Nevada National Security Site

2. National Cancer Institute: Fallout Exposure Estimates

3. Atomic Heritage Foundation